All these were placed under the control of the President and Council of the Surat factory, who had also the power to control the Company’s trade with the Red Sea ports and Persia. English factories were also started at Broach and Baroda with the object of purchasing at first hand the piece goods manufactured in the localities, and at Agra, in order to sell broad cloth to the officers of the imperial court and to buy indigo, the best quality of which was manufactured at Biyana. In 1668 Bombay was transferred to the East India Company by Charles II, who had got it from the Portuguese as a part of the dowry of his wife Catherine of Braganza, at an annual rental of 10 pounds. Bombay gradually grew more and more prosperous and became so important that in 1687 it superseded Surat as the chief settlement of the English on the west coast.

On the southern coast the English had established a factory at Masulipatam, the principal port of the kingdom of Golkunda, in 1611 in order to purchase the locally woven piece goods, which they exported to Persia and Bantam. But being much troubled there by the opposition of the Dutch and the frequent demands of the local officials, they opened another factory in 1626 at Armagaon, a few miles north of the Dutch settlement of Pulicat.

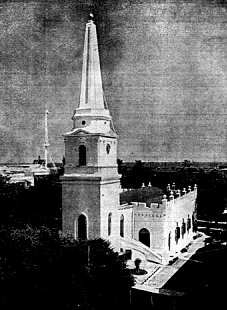

Here also they were put to various inconveniences, and so turned their attention again to Masulipatam, and to their great advantage the Sultan of Golkunda granted them the “Golden Firman” in A.D. 1632 by which they were allowed to trade freely in the ports belonging to the kingdom of Golkunda on payment of duties worth 500 pagodas a year. These terms were repeated in another firman of A.D. 1634. But this did not relieve the English traders from the demands of local officers and they looked for a more advantageous place. In A.D. 1639 Francis Day obtained the lease of Madras from the ruler of Chandragiri, representative of the ruined Vijayanagar Empire, and built there a fortified factory which came to be known as Fort St. George. Fort St. George soon superseded Masulipatam as headquarters of the English settlements on the Coromandel Coast.

Here also they were put to various inconveniences, and so turned their attention again to Masulipatam, and to their great advantage the Sultan of Golkunda granted them the “Golden Firman” in A.D. 1632 by which they were allowed to trade freely in the ports belonging to the kingdom of Golkunda on payment of duties worth 500 pagodas a year. These terms were repeated in another firman of A.D. 1634. But this did not relieve the English traders from the demands of local officers and they looked for a more advantageous place. In A.D. 1639 Francis Day obtained the lease of Madras from the ruler of Chandragiri, representative of the ruined Vijayanagar Empire, and built there a fortified factory which came to be known as Fort St. George. Fort St. George soon superseded Masulipatam as headquarters of the English settlements on the Coromandel Coast.

The next stage in the growth of English influence was their expansion in the north-east. Factories had been started at Hariharpur in the Mahanadi Delta and at Balasore in A.D. 1633. A factory was established at Hugli, under Mr. Bridgeman, in 1651, and soon others were opened at Patna and Cassimbazar. The principal articles of the English trade in Bengal during this period were silk, cotton piece goods saltpetre and sugar, but owing to the irregular private trade of the factory the Company did not derive much advantage before some time had elapsed. In 1658 all the settlements in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and on the Coromandel Coast, were made subordinate to Fort St. George.

For various reasons, the prospects of the Company’s trade at Madras and Surat were not very bright during the first half of the seventeenth century. But its misfortunes disappeared during the second half of that century, owing to changes in the policy of the home government. The charter granted by Cromwell in 1657 gave it fresh opportunities. The thirty years following the Restoration of 1660 formed a period of expansion and prosperity. Both Charles II and James II confirmed the old privileges of the Company and extended its powers. At the same time, the establishment of a permanent joint-stock backing greatly relieved the Company of its past financial difficulties.

The Company’s policy in India also changed during this period. A peaceful trading body was transformed into a power eager to establish its own position by territorial acquisitions, largely in view of the political disorders in the country. The long warfare between the imperial forces, the Marathas and the other Deccan states, the Maratha raids on Surat in 1664 and 1670, the weak government of the Mughul viceroys in Bengal, which became exposed to grave internal as well as external danger, the disturbances caused by the Malabar pirates and the consequent necessity of defence made the change inevitable. Gerald Aungier, successor of Sir George Oxenden as President at Surat and Governor of Bombay since 1669, wrote to the Court of Directors that “the times now require you to manage your general commerce with the sword in your hands”. In the course of a few years the Directors approved of this change in the Company’s policy and wrote to the Chief at Madras in December, 1687, ” to establish such a politie of civil and military power, and create and secure such a large revenue to secure both . . . as may be the foundation of a large, well grounded, secure English dominion in India for all time to come “. Sir Josiah Child, the dominant personality in the affairs of the Company in the time of the later Stuarts was largely responsible for this new policy, though it did not actually originate with him. In pursuance of it, in December, 1688, Sir John Child, his brother, blockaded Bombay and the Mughul ports on the western coast, seized many Mughul vessels and sent his captain to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf “to arrest the pilgrimage traffic to Mecca”. But the English had underestimated the force of the Mughul Empire, which was still very strong and could be effectively exercised. Sir John Child at last appealed for pardon to Aurangazeb, who granted it (February, 1690), and also a licence for English trade when the English agreed to restore all the captured Mughul ships and to pay one-and-a-half lacs of rupees in compensation.

The Company’s policy in India also changed during this period. A peaceful trading body was transformed into a power eager to establish its own position by territorial acquisitions, largely in view of the political disorders in the country. The long warfare between the imperial forces, the Marathas and the other Deccan states, the Maratha raids on Surat in 1664 and 1670, the weak government of the Mughul viceroys in Bengal, which became exposed to grave internal as well as external danger, the disturbances caused by the Malabar pirates and the consequent necessity of defence made the change inevitable. Gerald Aungier, successor of Sir George Oxenden as President at Surat and Governor of Bombay since 1669, wrote to the Court of Directors that “the times now require you to manage your general commerce with the sword in your hands”. In the course of a few years the Directors approved of this change in the Company’s policy and wrote to the Chief at Madras in December, 1687, ” to establish such a politie of civil and military power, and create and secure such a large revenue to secure both . . . as may be the foundation of a large, well grounded, secure English dominion in India for all time to come “. Sir Josiah Child, the dominant personality in the affairs of the Company in the time of the later Stuarts was largely responsible for this new policy, though it did not actually originate with him. In pursuance of it, in December, 1688, Sir John Child, his brother, blockaded Bombay and the Mughul ports on the western coast, seized many Mughul vessels and sent his captain to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf “to arrest the pilgrimage traffic to Mecca”. But the English had underestimated the force of the Mughul Empire, which was still very strong and could be effectively exercised. Sir John Child at last appealed for pardon to Aurangazeb, who granted it (February, 1690), and also a licence for English trade when the English agreed to restore all the captured Mughul ships and to pay one-and-a-half lacs of rupees in compensation.