Art and Architecture

Architecture

As in literature and religion, so in art and architecture, the Mughul period was not entirely an age of innovation and renaissance, but of a continuation and culmination of processes that had their beginnings in the later Turko-Afghan period. In fact, the art and architecture of the period after 1526, as also of the preceding period, represent a happy mingling of Muslim and Hindu art traditions and elements.

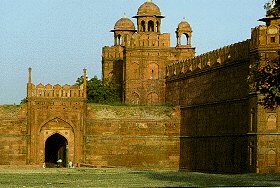

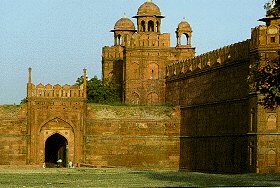

With the exception of Aurangzeb, whose puritanism could not reconcile itself with patronage of art, all the early Mughul rulers of India were great builders. Brief though his Indian reign was, Babur could make time to criticise in his Memoirs the art of building in Hindustan and think of constructing edifies. He is said to have invited from Constantinople pupils of the famous Albanian architect, Sinan, to work on mosques and other monuments in India. “It is, however, very unlikely,” remarks Mr. Percy Brown, that this proposal ever came to anything, because had any member of this famous school taken service under the Mughuls, traces of the influence of the Byzantine style would be observable. But there is none. Babur employed Indian stone-masons to construct his buildings. He himself states in his Memoirs that “680 men worked daily on his buildings at Agra, and that nearly 1,500 were employed daily on his buildings at Sikri, Biyana, Dholpur, Gwalior and Kiul”. The larger edifices of Babur have entirely disappeared. Three minor ones have survived, one of which is a commemorative mosque in the Kabuli Bag at Panipat (1526), another the Jami Masjid at Sambhal (1526) in Rohilkhand, and the third a mosque within the old Lodi fort at Agra. Of the reign of the unlucky emperor Humayun, only two structures remain in a semi-dilapidated condition, one mosque at Agra, and the other a massive well-proportioned mosque at Fathbad in the Hissar district of the Punjab, built about A.D. 1540 with enamelled tile decoration in the Persian manner. It should be noted here that this “Persian” or rather “Mongol” trait, was not brought to India for the first time by Humayun, but had already been present in the Bahmani kingdom in the later half of the fifteenth century. The short reign of the Indo-Afghan revivalist Sher Shah is a period of transition in the history of Indian architecture. The two remaining gateways of his projected walled capital at Delhi, which could not be completed owing to ‘his untimely death, and the citadel known as the Purana Qil’a, exhibit” a more refined and artistically ornate type of edifice than had prevailed for some time “. The mosque called the Qil’a-i-Kuhna Masjid, built in 1554 within the walls, deserves a high place among the buildings of Northern India for its brilliant architectural qualities. Sher Shah’s mausoleum, built on a high plinth in the midst of a lake at Sasaram in the Shahabad district of Bihar, is a marvel of Indo-Moslem architecture, both from the standpoint of design and dignity, and shows a happy combination of Hindu and Muslim architectural ideas. Thus not only in government, but also in culture and art, the great Afghan prepared the way for the great Mughul, Akbar.

With the exception of Aurangzeb, whose puritanism could not reconcile itself with patronage of art, all the early Mughul rulers of India were great builders. Brief though his Indian reign was, Babur could make time to criticise in his Memoirs the art of building in Hindustan and think of constructing edifies. He is said to have invited from Constantinople pupils of the famous Albanian architect, Sinan, to work on mosques and other monuments in India. “It is, however, very unlikely,” remarks Mr. Percy Brown, that this proposal ever came to anything, because had any member of this famous school taken service under the Mughuls, traces of the influence of the Byzantine style would be observable. But there is none. Babur employed Indian stone-masons to construct his buildings. He himself states in his Memoirs that “680 men worked daily on his buildings at Agra, and that nearly 1,500 were employed daily on his buildings at Sikri, Biyana, Dholpur, Gwalior and Kiul”. The larger edifices of Babur have entirely disappeared. Three minor ones have survived, one of which is a commemorative mosque in the Kabuli Bag at Panipat (1526), another the Jami Masjid at Sambhal (1526) in Rohilkhand, and the third a mosque within the old Lodi fort at Agra. Of the reign of the unlucky emperor Humayun, only two structures remain in a semi-dilapidated condition, one mosque at Agra, and the other a massive well-proportioned mosque at Fathbad in the Hissar district of the Punjab, built about A.D. 1540 with enamelled tile decoration in the Persian manner. It should be noted here that this “Persian” or rather “Mongol” trait, was not brought to India for the first time by Humayun, but had already been present in the Bahmani kingdom in the later half of the fifteenth century. The short reign of the Indo-Afghan revivalist Sher Shah is a period of transition in the history of Indian architecture. The two remaining gateways of his projected walled capital at Delhi, which could not be completed owing to ‘his untimely death, and the citadel known as the Purana Qil’a, exhibit” a more refined and artistically ornate type of edifice than had prevailed for some time “. The mosque called the Qil’a-i-Kuhna Masjid, built in 1554 within the walls, deserves a high place among the buildings of Northern India for its brilliant architectural qualities. Sher Shah’s mausoleum, built on a high plinth in the midst of a lake at Sasaram in the Shahabad district of Bihar, is a marvel of Indo-Moslem architecture, both from the standpoint of design and dignity, and shows a happy combination of Hindu and Muslim architectural ideas. Thus not only in government, but also in culture and art, the great Afghan prepared the way for the great Mughul, Akbar.

Akbar’s reign saw a remarkable development of architecture. With his usual thoroughness, the Emperor mastered every detail of the art; and, with a liberal and synthetic mind he supplied himself with artistic ideas from different sources, which were given a practical shape by the expert craftsmen he gathered around him. Abul Fazl justly observes that his sovereign “planned splendid edifices and dressed the work of his mind and heart in the garment of stone and clay”. Fergugson aptly remarked that Fathpur Sikri “was a reflex of the mind of a great man”. Akbar’s activities were not confined only to the great masterpieces of architecture; but he also built a number of forts, villas, towers, sarais, schools, tanks and wells. While still adhering to Persian ideas, which he inherited from his mother, born of a Persian Shaikh family of Jam, his tolerance of the Hindus, sympathy with their culture, and the policy of winning them over to his cause, led him to use Hindu styles of architecture in many of his buildings, the decorative features of which are copies of those found in the Hindu and Jaina temples. It is strikingly illustrated in the Jahangiri Mahal, in Agra fort, with its square pillars and bracket capitals, and rows of small arches built according to the Hindu design without voussoirs; in many of the buildings of Fathpur Sikri, the imperial capital from 1569 to 1584; and also in the Lahore fort. Even in the famous mausoleum of Humayun at Old Delhi, completed early in A.D. 1569, which is usually considered to have displayed influences of Persian art, the ground-plan of the tomb is Indian, the free use of white marble in the outward appearance of the edifice is Indian, and the coloured tile decoration, used so much by Persian builders, is absent. The most magnificent of the Emperor’s buildings at Fathpur Sikri are Jodha Bai’s palace and two other residential buildings, said to have been constructed to accommodate his queens; the Diwan-i-‘Am or the Emperor’s office, of Hindu design with a projecting veranda roof over a colonnade; the wonderful Diwan-i- Khas or Hall of private audience, of distinctly Indian character in planning construction and ornament; the marble mosque known as the Jami `Masjid, described by Fergusson as “a romance in stone”; the Buland Darwaza or the massive triumphal archway at the southern gate of the mosque, built of marble and sandstone to commemorate Akbar’s conquest of Gujarat; and the pyramidal structure in five storeys known as the Panch Mahal, showing continuation of the plan of the Indian Buddhist viharas which still exist in certain parts of India.

Akbar’s reign saw a remarkable development of architecture. With his usual thoroughness, the Emperor mastered every detail of the art; and, with a liberal and synthetic mind he supplied himself with artistic ideas from different sources, which were given a practical shape by the expert craftsmen he gathered around him. Abul Fazl justly observes that his sovereign “planned splendid edifices and dressed the work of his mind and heart in the garment of stone and clay”. Fergugson aptly remarked that Fathpur Sikri “was a reflex of the mind of a great man”. Akbar’s activities were not confined only to the great masterpieces of architecture; but he also built a number of forts, villas, towers, sarais, schools, tanks and wells. While still adhering to Persian ideas, which he inherited from his mother, born of a Persian Shaikh family of Jam, his tolerance of the Hindus, sympathy with their culture, and the policy of winning them over to his cause, led him to use Hindu styles of architecture in many of his buildings, the decorative features of which are copies of those found in the Hindu and Jaina temples. It is strikingly illustrated in the Jahangiri Mahal, in Agra fort, with its square pillars and bracket capitals, and rows of small arches built according to the Hindu design without voussoirs; in many of the buildings of Fathpur Sikri, the imperial capital from 1569 to 1584; and also in the Lahore fort. Even in the famous mausoleum of Humayun at Old Delhi, completed early in A.D. 1569, which is usually considered to have displayed influences of Persian art, the ground-plan of the tomb is Indian, the free use of white marble in the outward appearance of the edifice is Indian, and the coloured tile decoration, used so much by Persian builders, is absent. The most magnificent of the Emperor’s buildings at Fathpur Sikri are Jodha Bai’s palace and two other residential buildings, said to have been constructed to accommodate his queens; the Diwan-i-‘Am or the Emperor’s office, of Hindu design with a projecting veranda roof over a colonnade; the wonderful Diwan-i- Khas or Hall of private audience, of distinctly Indian character in planning construction and ornament; the marble mosque known as the Jami `Masjid, described by Fergusson as “a romance in stone”; the Buland Darwaza or the massive triumphal archway at the southern gate of the mosque, built of marble and sandstone to commemorate Akbar’s conquest of Gujarat; and the pyramidal structure in five storeys known as the Panch Mahal, showing continuation of the plan of the Indian Buddhist viharas which still exist in certain parts of India.

Two other remarkable buildings of the period are the Palace of Forty Pillars at Allahabad and Akbar’s mausoleum at Sikandara. The palace at Allahabad, the construction of which according to William Finch, took forty years, and engaged 5,000 to 20,000 workmen of different denominations, is of a definitely Indian design with its projecting veranda-roof “supported on rows of Hindu pillars “. The colossal structure of Akbar’s mausoleum at Sikandara, planned in the Emperor’s lifetime but executed between A.D. 1605 and 1613, consists of five terraces diminishing as they ascend with a vaulted roof to the topmost story of white marble, and it is thought that a central dome was originally intended to be built over the cenotaph. The Indian design in this structure was inspired by the Buddhist viharas of India and also probably by Khmer architecture found in Cochin-China.

With the exception of Aurangzeb, whose puritanism could not reconcile itself with patronage of art, all the early Mughul rulers of India were great builders. Brief though his Indian reign was, Babur could make time to criticise in his Memoirs the art of building in Hindustan and think of constructing edifies. He is said to have invited from Constantinople pupils of the famous Albanian architect, Sinan, to work on mosques and other monuments in India. “It is, however, very unlikely,” remarks Mr. Percy Brown, that this proposal ever came to anything, because had any member of this famous school taken service under the Mughuls, traces of the influence of the Byzantine style would be observable. But there is none. Babur employed Indian stone-masons to construct his buildings. He himself states in his Memoirs that “680 men worked daily on his buildings at Agra, and that nearly 1,500 were employed daily on his buildings at Sikri, Biyana, Dholpur, Gwalior and Kiul”. The larger edifices of Babur have entirely disappeared. Three minor ones have survived, one of which is a commemorative mosque in the Kabuli Bag at Panipat (1526), another the Jami Masjid at Sambhal (1526) in Rohilkhand, and the third a mosque within the old Lodi fort at Agra. Of the reign of the unlucky emperor Humayun, only two structures remain in a semi-dilapidated condition, one mosque at Agra, and the other a massive well-proportioned mosque at Fathbad in the Hissar district of the Punjab, built about A.D. 1540 with enamelled tile decoration in the Persian manner. It should be noted here that this “Persian” or rather “Mongol” trait, was not brought to India for the first time by Humayun, but had already been present in the Bahmani kingdom in the later half of the fifteenth century. The short reign of the Indo-Afghan revivalist Sher Shah is a period of transition in the history of Indian architecture. The two remaining gateways of his projected walled capital at Delhi, which could not be completed owing to ‘his untimely death, and the citadel known as the Purana Qil’a, exhibit” a more refined and artistically ornate type of edifice than had prevailed for some time “. The mosque called the Qil’a-i-Kuhna Masjid, built in 1554 within the walls, deserves a high place among the buildings of Northern India for its brilliant architectural qualities. Sher Shah’s mausoleum, built on a high plinth in the midst of a lake at Sasaram in the Shahabad district of Bihar, is a marvel of Indo-Moslem architecture, both from the standpoint of design and dignity, and shows a happy combination of Hindu and Muslim architectural ideas. Thus not only in government, but also in culture and art, the great Afghan prepared the way for the great Mughul, Akbar.

With the exception of Aurangzeb, whose puritanism could not reconcile itself with patronage of art, all the early Mughul rulers of India were great builders. Brief though his Indian reign was, Babur could make time to criticise in his Memoirs the art of building in Hindustan and think of constructing edifies. He is said to have invited from Constantinople pupils of the famous Albanian architect, Sinan, to work on mosques and other monuments in India. “It is, however, very unlikely,” remarks Mr. Percy Brown, that this proposal ever came to anything, because had any member of this famous school taken service under the Mughuls, traces of the influence of the Byzantine style would be observable. But there is none. Babur employed Indian stone-masons to construct his buildings. He himself states in his Memoirs that “680 men worked daily on his buildings at Agra, and that nearly 1,500 were employed daily on his buildings at Sikri, Biyana, Dholpur, Gwalior and Kiul”. The larger edifices of Babur have entirely disappeared. Three minor ones have survived, one of which is a commemorative mosque in the Kabuli Bag at Panipat (1526), another the Jami Masjid at Sambhal (1526) in Rohilkhand, and the third a mosque within the old Lodi fort at Agra. Of the reign of the unlucky emperor Humayun, only two structures remain in a semi-dilapidated condition, one mosque at Agra, and the other a massive well-proportioned mosque at Fathbad in the Hissar district of the Punjab, built about A.D. 1540 with enamelled tile decoration in the Persian manner. It should be noted here that this “Persian” or rather “Mongol” trait, was not brought to India for the first time by Humayun, but had already been present in the Bahmani kingdom in the later half of the fifteenth century. The short reign of the Indo-Afghan revivalist Sher Shah is a period of transition in the history of Indian architecture. The two remaining gateways of his projected walled capital at Delhi, which could not be completed owing to ‘his untimely death, and the citadel known as the Purana Qil’a, exhibit” a more refined and artistically ornate type of edifice than had prevailed for some time “. The mosque called the Qil’a-i-Kuhna Masjid, built in 1554 within the walls, deserves a high place among the buildings of Northern India for its brilliant architectural qualities. Sher Shah’s mausoleum, built on a high plinth in the midst of a lake at Sasaram in the Shahabad district of Bihar, is a marvel of Indo-Moslem architecture, both from the standpoint of design and dignity, and shows a happy combination of Hindu and Muslim architectural ideas. Thus not only in government, but also in culture and art, the great Afghan prepared the way for the great Mughul, Akbar.