The Pre-historic Period

The most artistic objects at Mohenjo-Daro are no doubt the seal engravings, portraying animals like the humped bull, the buffalo, the bison, etc. (Sir John Marshall remarks on these, as also on two stone statues found at Harappa.

Maurya Period-the Origin of Art

The earliest ruins of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro have been assigned to a period not later than 2700 BC. For more than two thousand years after that we possess no ancient monuments that deserve any serious consideration.

In the historical period, we have ruins of monuments that may be referred to as early a period as 500 BC. But it is only in the age of Asoka, the great Maurya emperor, that we come across monuments of high quality in large number which enable us to form a definite idea about the nature of Indian art.

The finest examples of Asokan art are furnished by the monolithic pillars on which his edicts are engraved. Each pillar consists of a shaft or column, made of one piece of stone, supporting a capitallumbini ashoka pillar made of another single piece of stone.  The round and slightly tapering shaft, made of sandstone, is highly polished and very graceful in its proportions. The capital, equally highly polished, consists of one or more animal figures in the round, resting on an abacus engraved with sculptures in relief; and below this is the inverted lotus, which is usually, though perhaps wrongly, called the Persepolitan Bell. A high degree of knowledge of engineering was displayed in cutting these huge blocks of stone and removing them hundreds of miles from the quarry, and sometimes to the top of a hill. Extraordinary technical skill was shown in cutting and chiselling the stone with wonderful accuracy and in imparting the lustrous polish to the whole surface. But these pale into insignificance before the high artistic merits of the figures, which exhibit realistic modelling and movement of a very high order. The capital of the Sarnath Pillar is undoubtedly the best of the series. The figures of four lions standing back to back, and the smaller figures of animals in relief OD the abacus, all show a highly advanced form of art and their remarkable beauty and vigour have elicited the highest praise from all the art critics of the world. The late Dr. V. A. Smith made the following observation on the Sarnath capital:

The round and slightly tapering shaft, made of sandstone, is highly polished and very graceful in its proportions. The capital, equally highly polished, consists of one or more animal figures in the round, resting on an abacus engraved with sculptures in relief; and below this is the inverted lotus, which is usually, though perhaps wrongly, called the Persepolitan Bell. A high degree of knowledge of engineering was displayed in cutting these huge blocks of stone and removing them hundreds of miles from the quarry, and sometimes to the top of a hill. Extraordinary technical skill was shown in cutting and chiselling the stone with wonderful accuracy and in imparting the lustrous polish to the whole surface. But these pale into insignificance before the high artistic merits of the figures, which exhibit realistic modelling and movement of a very high order. The capital of the Sarnath Pillar is undoubtedly the best of the series. The figures of four lions standing back to back, and the smaller figures of animals in relief OD the abacus, all show a highly advanced form of art and their remarkable beauty and vigour have elicited the highest praise from all the art critics of the world. The late Dr. V. A. Smith made the following observation on the Sarnath capital:

“It would be difficult to find in any country an example of ancient animal sculpture superior or even equal to this beautiful work of art, which successfully combines realistic modelling with ideal dignity and is finished in every detail with perfect accuracy.”

Many other pillars of Asoka, though inferior to that of Sarnath, possess remarkable beauty. It may be mentioned in this connection that the jewellery of the Maurya period also exhibits a high degree of technical skill and proficiency.

As compared with sculpture, the architectural remains of the Maurya period are very poor. Contemporary Greek writers refer to magnificent palaces in the capital city of Pataliputra and regard them as the finest and grandest in the whole world. Some seven hundred years later the Mauryan edifices inspired awe and admiration in the heart of the Chinese traveller, Fa Hien. But these noble buildings have utterly perished. Recent excavations on the site have laid bare their ruins, the most remarkable being those of a hundred-pillared hall.

The extant architectural remains consist, besides a small monolithic stone rail round a stupa at Sarnath, mainly of the rock-cut Chaitya halls in the Barabar hills and neighbouring localities in the Bihar subdivision of the Patna district. Although excavated in the hardest rock, the walls of these caves are polished like glass.

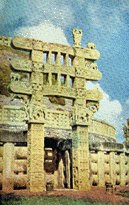

Asoka also built quite a large number of stupas. The stupa is a solid domical structure of brick or stone,sanchi stupa resting on a round base. It was sometimes surrounded by a plain or ornamented stone railing with one or more gateways, which were often of highly elaborate pattern and decorated with sculptures. Tradition credits Asoka with building 84,000 stupas all over India and Afghanistan but they have almost entirely perished. Some of them, enclosed and enlarged at later times, perhaps still exist, the most famous example being the big stupa at Sanchi, in Bhopal State, not far from Bhilsa. The diameter of the present stupa is 121 1/2 feet, the height about 77 1/2 feet, and the massive stone railing which encloses it is 11 feet high. According to Sir John Marshall, the original brick stupa built by Asoka was probably of not more than half the present dimensions, which were subsequently enlarged by the addition of a stone casing faced with concrete. The present railing also replaced the older and smaller one. A similar fate has possibly overtaken many other stupas of Asoka.

Asoka also built quite a large number of stupas. The stupa is a solid domical structure of brick or stone,sanchi stupa resting on a round base. It was sometimes surrounded by a plain or ornamented stone railing with one or more gateways, which were often of highly elaborate pattern and decorated with sculptures. Tradition credits Asoka with building 84,000 stupas all over India and Afghanistan but they have almost entirely perished. Some of them, enclosed and enlarged at later times, perhaps still exist, the most famous example being the big stupa at Sanchi, in Bhopal State, not far from Bhilsa. The diameter of the present stupa is 121 1/2 feet, the height about 77 1/2 feet, and the massive stone railing which encloses it is 11 feet high. According to Sir John Marshall, the original brick stupa built by Asoka was probably of not more than half the present dimensions, which were subsequently enlarged by the addition of a stone casing faced with concrete. The present railing also replaced the older and smaller one. A similar fate has possibly overtaken many other stupas of Asoka.

It is quite evident from what has been said above, that Maurya art exhibits in many respects an advanced stage of development in the evolution of Indian art. The artists of Asoka were by no means novices, and there must have been a long history of artistic effort behind them. How are we then to explain the almost total absence of specimens of Indian art before c. 250 BC.

This is the problem which faces us at the very beginning of our study of Indian art–highly finished specimens of art, belonging to such remotely distant periods as 2700 BC and 250 BC. with little to fill up the long intervening gap.

We are not in a position to solve this problem until more data are available. In the meantime we can only consider various possibilities.