India is the name given to the vast peninsula which the continent of Asia throws out to the south of the magnificent mountain ranges that stretch in a sword-like curve across the southern border of Tibet. This huge expanse of territory, which deserves the name of a sub-continent, has the shape of an irregular quadrilateral. Ancient geographers referred to it as being “constituted with a four-fold conformation” (chatuh, samsthana smsthitam) ” on its south and west and east is the Great Ocean, the Himavat range stretches along its north like the string of a bow”. The lofty mountain chain in the north—to which the name Himavat is applied in the above passage—includes not only the snow—capped ridges of the Himalayas but also their less elevated offshoots—the Patkai, Lushai and Chittagong Hills in the east, and the Sulaiman and Kirthar ranges in the west.

These lead down to the sea and separate the country from the wooded valley of the Irrawaddy on the one hand and the hilly tableland of Iran on the other.

Politically , the Indian empire as it existed before August 15, 1947, extended beyond these naturalAsia. boundaries at several points and included not only Baluchistan beyond the Kirthar ranges, but also some smaller areas that lay scattered in the Bay of Bengal. With the exception of the out laying territories beyond the seas, the whole of the vast region described above lay roughly between Long. 61° and 97° E. and Lat. 8° and 37° N. Its greatest length was about 2,900 kilometers, and its breadth not less than 2,190 kilometers. The total area of the empire, excluding Burma which was constituted as a separated unit under the Government of India Act of 1935, might be put at 4,095,000 square kilometers and the population inhabiting it, according to the census of 1941, the last taken before the creation of Pakistan, at about three hundred and eighty nine millions.

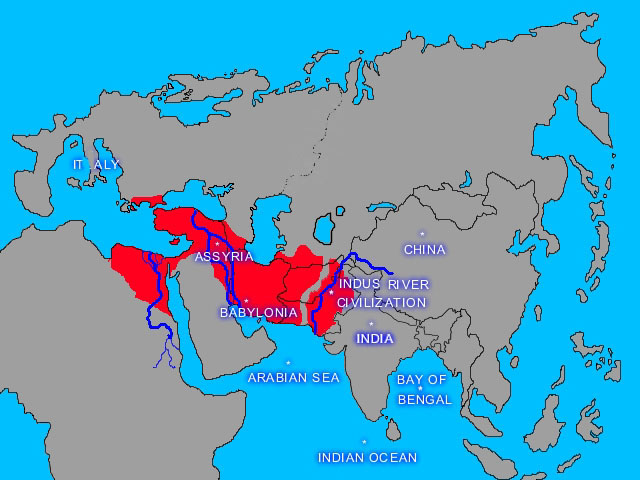

The sub-continent of India, stretching from the Himalayas to the sea, is known to the Hindus as Bharata-Varsha or the land of Bharata, a king famous in Puranic tradition. It was said to form part of “larger unit called Jambu-dvipa which was considered, to be the innermost of seven concentric island-continents into which the earth, as conceived by Hindu cosmographers, was supposed to have been divided. The Puranic account of these insular continents contains a good deal of what is fanciful, but early Buddhist evidence suggests that Jambu-dvipa was a territorial designation actually in use from the third century BC at the latest, and was applied to that part of Asia, outside China, throughout which the prowess of the great imperial family of the Mauryas made itself felt. The name “India” was applied to the country by the Greeks. It corresponds to the “Hi(n)du” of the old Persian epigraphs. Like “Sapta sindhavah” and “Hapta Hindu”—the appellations of the, country of the Aryans in the Veda and the Vendidad—it is derived from the Sindhu (the Indus), the great river which constitutes—the most imposing feature of that part of the sub-continent which seems to have been the cradle of its earliest known civilization. Closely connected with “Hindu” are the later designations “Hind” and “Hindusthan” as found in the pages of medieval writers.

India proper, excluding its outlying dependencies, is divided primarily into four distinct regions, viz., (1) the hill country of the north, styled Parvatasrayin in the Puranas, stretching from the swampy jungles of the Tarai to the crest of the Himalayas and affording space for the upland territories of Kashmir, Kangra, Tehri, Kumaun, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan; (2) the great northern plain embracing the flat wheat-producing valleys of the Indus and its tributaries, the sandy deserts of Sind and Rajputana as well as the fertile tracts watered by the Ganges, the Jumna, and the Brahmaputra; (3) the plateau of South Central India and the Deccan stretching south of the Gangetic plain and shut in from the rest of the peninsula by the main range of the Paripatra, roughly the Western Vindhyas, the Vindhyas proper, the Sahyadri or the Western Ghats and the Mahendra or the Eastern Ghats; and (4) the long and narrow maritime plains of the south extending from the Ghats to the sea and containing the rich ports of the Konkan and Malabar, as well as the fertile deltas of the Godavari, the Krishna and the Kaveri.

These territorial compartments marked by the hand of nature do not exactly coincide with the traditional divisions of the country known to antiquity. In ancient literature we have reference to a fivefold division of India. In the centre of the Indo-Gangetic plain was the Madhya-desa stretching, according to the Brahmanical accounts, from the river Saraswati, which flowed past Thanesar and Pehoa (ancient Prithudaka), to Allahabad and Benares, and, according to the early records of the Buddhists, to the Rajmahal Hills. The western part of this area was known as the Brahmarshi-desa, and the entire region was roughly equivalent to Aryavarta as described in the grammar of Patanjali. But the denotation of the latter term is wider in some law-books which take it to mean the whole of the vast territory lying between the Himalayas and the Vindhyas and extending from sea to sea. To the north of the Madhya-desa, beyond Pehoa, lay Uttarapatha or Udichya (North-west India), to its west Aparanta or Pratichya (Western India), to its south Dakshinapatha or the Deccan, and to its east Purva-desa or Prachya, the Prasii of Alexander’s historians. The term Uttarapatha was at times applied to the whole of Northern India, and Dakshinapatha was in some ancient works restricted to the upper Deccan north of the Krishna, the far south being termed Tamilakam or the Tamil country, while Purva-desa in early times included the eastern part of the “middle region” beyond the Antarvedi or the Gangetic Doab. To the five primary divisions the Puranas sometimes add two others, viz., the Parvasrayin or HimaIayan tract, and the Vindhyan region.